Research

Google Scholar NIxNLlUAAAAJ

ORCID 0000-0003-1293-5578

Scopus 6701402577

Links to: Academia.edu, Researchgate, SSRN, REPEC

I then moved on to issues of economic growth and development, including a paper written in the mid-2000s on the PRC’s economic growth through 2025, which, as it has turned out since, rather accurately predicted growth in the subsequent periods 2010-15 and 2015-20.

The frequent use of PRC data invariably led to a deeper understanding of the quality of the PRC’s major macroeconomic data series. In a succession of papers through the mid-2010s I exposed the pitfalls of certain official PRC statistics but also found that some statistics, such as national income accounts statistics (including gross domestic product, GDP), are about as good as they can be given the limitations to data compilation in the PRC. Further papers constructed data used in China research such as physical capital measures and comparable provincial absolute price levels.

Eventually, I lost interest in the PRC’s official statistics. It’s not only the declining quality of PRC statistics and the inability to conduct conclusive double-checks. A big part of the PRC growth story may just be the story of marketization of previously household production (GDP does not consider household production) and standard rural-urban migration (into higher-productivity activities). Add to that the many well-known shortcomings of ‘gross domestic product’ as a measure of development or “well-being.” Analyzing ever more problematic data trying to say something about an increasingly meaningless construct (GDP) isn’t a very fulfilling exercise.

In the mid-2010s I began a project on economic development policies in underdeveloped regions of the PRC, documenting how economic development comes about, what the role of the government is, and what the consequences for the local populations are. For example, Daocheng County, located on the Tibetan Plateau in West Sichuan, strongly promoted tourism, leading to a heavy influx of Han immigrants while the living standards of the original, local Tibetan population continues to lag far behind.

I also pursued other interests such as the PRC’s industrial policies and their effects: The importance of these policies is over-interpreted in the West.

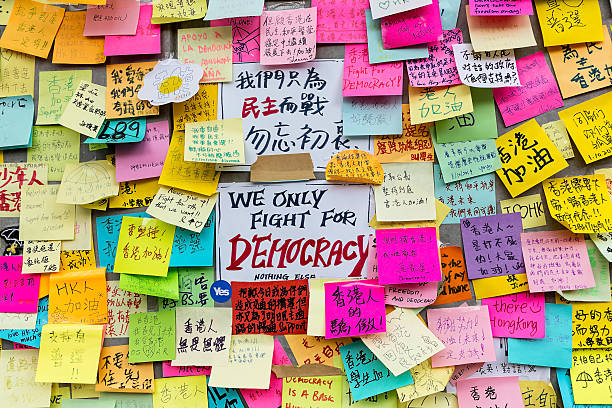

By the late 2010s I found it hard to sit on an upper floor of the ivory tower pouring over PRC documents when the ground floor was on fire. What’s the point of exploring a narrow PRC economics topic if there are freedom- if not life-threatening tectonic shifts occurring right underneath my feet? I wrote some short pieces on academic freedom in Hong Kong, continuing along a trajectory that began with a number of essays on the totalitarian state of Hong Kong University of Science & Technology, including its ‘Gleichschaltung,’ and some school- and university-internal notes.

For a list of my publications and other writings please go to https://carstenholz.people.ust.hk/. For my CV see here.